The System of Interpersonal Interactions:

The System of Interpersonal Interactions negotiates interpersonal access, influencing content creation through the distribution of social capital and power.

Simming content is shaped by the system of interpersonal interactions in a variety of ways, but one key construct remains central: regulating interpersonal access. In this system, connecting or obtaining access to "the right" interpersonal interactions is a gateway to the growth of influence and power, the spread of one's content, and the shaping of the ecology.

In the Simming ecology, social ties are formed through contact, during which parties negotiate the balance of power and intimacy. The kinds of ties that we can observe vary depending on the positioning of the parties involved. This power and intimacy interplay is a component of Cooper's definition of the System of Interpersonal Interactions: "the means by which writers regulate their access to one another" ("The Ecology of Writing" 8). Cooper argues that through this system, writers define their position in comparison to each other. This negotiation is constantly in flux, and according to Cooper, it is determined by the things writers have in common (intimacy) and how much control one writer has over another writer (power)(Cooper 8). While Cooper's definition does account for more simple, one-on-one interactions, the negotiation she describes is complicated by the ways in which Simmers construct power. In the Simming Ecology, power and what this project refers to as "social capital" go hand-in-hand.

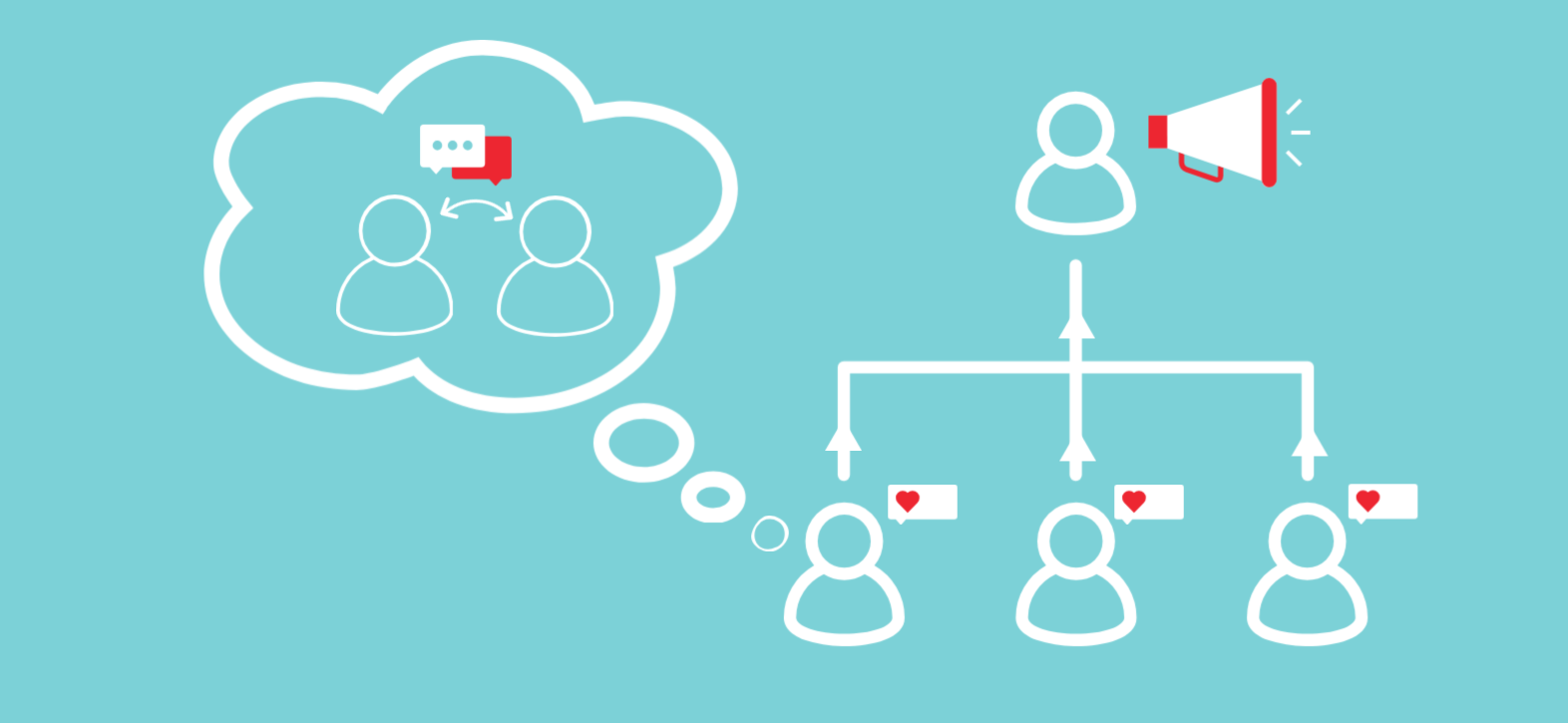

The relationship between power and social capital in the Simming ecology can be further illuminated by research on social capital in social networking sites. In their chapter "With a Little Help From My Friends: How Social Network Sites Affect Social Capital Processes," Ellison et al. draw from Putnam to define social capital as "benefits that can be attained from connections between people through their social networks" (127). In this piece, they explore the ways in which social capital is cultivated on Facebook, framing the discussion around "bridging" and "bonding" forms. Ellison et al. claim that "Whereas bridging social capital provides access to a wider range of information and diverse perspectives, bonding social capital is linked to social support and more substantive support, such as financial loans" (127). Here, Ellison et al.'s description aligns bonding ties with greater intimacy. Bonds with powerful people and organizations can provide the Simmer with access to more resources, as described in the YouTube video on the left. However, it is important to mention that the accumulation of bridging forms can provide significant social capital. Bridging is the kind of connection often associated with influencers and popular internet figures; further reach and exposure to more people in this form results in a reduced potential for two-way intimacy but increased access to information and interactions. Additionally, bridging ties on platforms like YouTube, Twitch, and Twitter can be asymmetrical. A common example of asymmentrical bridges would be the relationship between a relatively unrecognized Simmer and their investment in a prominent content creator. In this situation, only one party consents to "follow," and they perceive a stronger connection and greater intimacy than the potentially unaware, second party (Ellison et al. 140-141). "Bridging" and "bonding" connections, therefore, can speak to the different kinds of complex negotiations that Simmers have with power.

Through bridging and bonding connections, power becomes centralized with Simmers who have access to the most social capital. If a Simmer has thousands of engaged followers, their content and content creation practices (including how they navigate ecological systems) are observed by and extend influence to more people. Therefore, on the ecology's "spiderweb," their interactions pluck more strands and reverberate further to extend greater influence over the ecology as a whole.

Regulation of access can result in conflict when one Simmer attempts to form a connection with another who has more power and less shared intimacy. In these situations, the Simmer with less power may presume that they have more intimacy with the other party than what they do in actuality. In this case, rather than the formation of an equal, bidirectional "bridge" or "bond" tie, connections usually spring from the "follower" to the more popular content creator in a single direction to form an asymetrical bond. This can cause the "follower" party to perceive more intimacy than what actually exists.