Defining Ecological Systems

Cooper's "Ecology of Writing" is widely attributed as a shared disciplinary foundation for ecology theory; Dobrin describes it as "perhaps the most well-known work in ecology and composition studies" (Dobrin "Introduction" 3). This holds especially true in the lasting impact of Cooper's positioning of ecological influences as "systems."

Cooper's systems permit examination of actively developing sites and moments of writing:

"An important characteristic of ecological systems is that they are inherently dynamic; though their structures and content can be specified at a given moment, in real time they are constantly changing, limited only by parameters that are themselves subject to change over longer spans of time" (7).

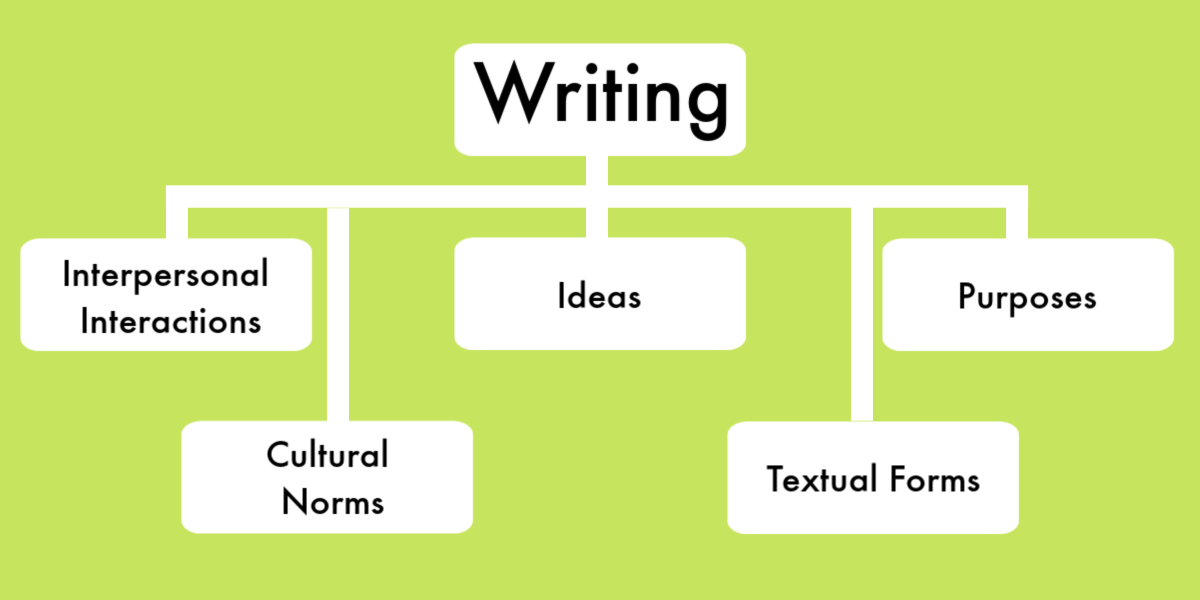

Defined to the left, Cooper's original framework locates five example systems--the system of interpersonal interactions, the system of ideas, the system of purposes, the system of cultural norms, and the system of textual forms ("The Ecology of Writing").

Ecologies are dynamic, and systems change over time. To see the systems I propose as being active in the Simming ecology, click here.

Ecologies are dynamic, and systems change over time. To see the systems I propose as being active in the Simming ecology, click here.

These original systems provide explanatory power for certain kinds of writing ecologies, but they do not encompass all writing. As Cooper says, her original, five proposed systems are a "heuristic, not a taxonomy" (2). Therefore, when applying this framework to new sites of writing, we must account for new or different systems.

Rather than cementing the model in "static and limited categories of contextual models," Cooper's systems are "dynamic" and "interlocking;" they work to "structure the social activity of writing" (7). Cooper's model accomodates the ways in which writing ecologies change. Therefore, as content creation ecologies evolve with new practices, materials, and writers, scholars can use Cooper's model to accomodate these rapidly-moving changes and analyze the otherwise-intangible.

While the Simming ecology is very different from the writing ecologies Cooper and her 1986 contemporaries would've imagined, Cooper's interconnected framework of systems in some ways anticipated the complex, hyper-collaborative composing environments of today. Thus, it offers valuable insights into the networked writing.